“Actually I think I know pretty much everything Donald Trump knows, except the ins and out of real estate wheeling and dealing. And I think I know pretty much what Gina Rinehart knows, except the ins and outs of iron ore prices and booking a big tractor. I feel I could probably learn those things. I wouldn’t want to, but I could.”

Ben Elton is sounding off about the disproportionate influence billionaires seem to be granted in Australia. A longtime Australian resident, the prolific author, playwright, comedian and director decries the “unhealthy” influence of the wealthy – people like Gina Rinehart, Clive Palmer and Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest – “as if there was some wisdom to being a massively wealthy individual, which clearly there isn’t”.

Speaking to Elton is great fun: he has opinions on just about everything and he’s not afraid to share them.

This is when he throws in the Donald: “Donald Trump is claiming that ‘because I’m a billionaire, I must know something that you don’t’ – I don’t think that’s the case. I think a homeless person definitely knows something I don’t; I think a mother or a father or a carer trying to bring up a disabled child, they know something I don’t.”

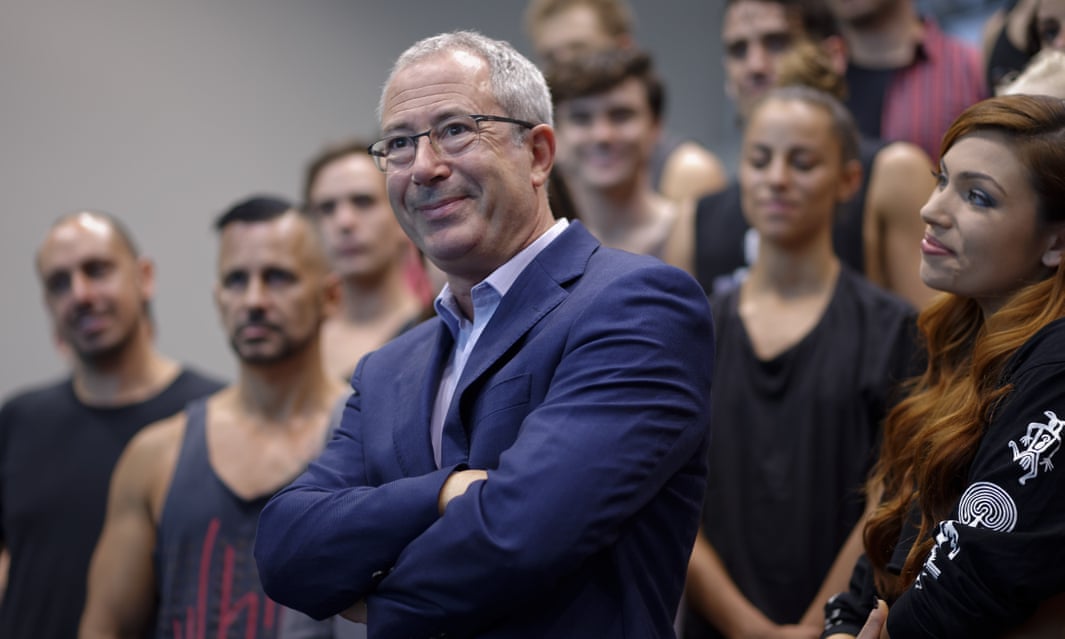

Elton is in Sydney for rehearsals of the new production of We Will Rock You, which opens next week. He wrote the musical in 2001 alongside Queen’s Brian May, Roger Taylor and John Deacon. But the musical is much more than a tribute show to the 1980s rock group: We Will Rock You is set in a dystopian future, where live music has been outlawed and musical instruments are forbidden.

The original production opened in London’s West End in May 2002; despite scathing reviews, it ran until May 2014. Australians also enjoyed it: the first international production opened in Melbourne in August 2003 and went on to tour Perth, Brisbane and Sydney.

This new production has the same costumes, choreography and plot, but has been updated. “The 5% we play with is quite a significant refresher for a big-scale musical,” says Elton.

We Will Rock You harks back to when Elton was approached in 2000 by the three remaining members of Queen to create a musical around their songs. Deciding against a biography of late lead singer Freddie Mercury, he instead wrote a plot around the chilling effects of the digitisation of music. More than a decade later, he says the central issue remains as relevant.

“I’m not a luddite, we can’t fight it – I’m not going to start throwing stones at Silicon Valley. But I do think we, as a culture and as a community, have to start to address the fact that social interaction has kept humanity sane for many thousands of years – the high street, meeting people, actually being a part of a living breathing community as opposed to living inside the internet,” Elton says.

People may be moving online for shopping, music and social media, but they still want to socialise, he says. “[People] still want to go out and meet, they still want to be part of life. We desperately need more music venues, and we need to get back to the time when Australia was creating its own rock’n’roll scene on an annual basis out of the pubs.”

It’s a particularly relevant conversation in Sydney, where live music venues are suffering the effects of the NSW government’s lockout laws. While Elton has sympathy for the anti-noise brigade, he says it’s part of the contract of living in a city. “If you lived in Montmartre during the belle époque, you couldn’t complain about the noise of Toulouse-Lautrec giggling with his latest prostitute.”

Although Elton is best known for his comedies (he describes We Will Rock You as “a full-on comedy”), he considers it important to tackle politics and social issues in his work. “I’ve always been energised by ideas. I’m not a very self-reflective person, I don’t tend to write about myself … Maybe I’m an empty, facile person, but I tend to be more interested in what’s going on around me than what’s going on inside me.”

Everything is political, he says: “The environment; the fact that we’re eating fruit that has been flown from California is a political issue; the clothes we wear cost less than the people who make them can live on – everything is a political issue. So in that respect, I’m always a political writer but that doesn’t mean I’m writing polemical stuff.”

Elton’s views on how arts funding is distributed are just provocative. “Personally I would put the money into grassroots; I think the high end will look after itself as it so obviously does in America,” he says.

Although Elton understands the UK arts funding model best, his comments have resonance in Australia, as state and federal governmentsgrapple with funding questions. Elton believes public arts funding is still essential but should be directed to those who need it most. “I’m not of the American view that it should all be done on sponsorship and business, but I think that money should probably go into regional works, small venues, education and the development of new work.”

Commercial producers like We Will Rock You’s John Frost also have an important role to play, Elton says. “There’s almost been a kind of sneer at the idea of a commercial producer, but it was commercial producers who first staged John Osborne and Samuel Beckett, commercial producers discovered the work of JB Priestley. Good playwriting, interesting playwriting will find an audience, and it doesn’t necessarily require a government committee to find those writers.”

Elton worries the current arts funding model skips over what he describes as “middlebrow” work. “Middlebrow writers like Shaw, Priestley, Coward, and – not to put myself in the same canon as those greats – but myself and Ray Cooney for instance, who are hoping to write intelligent work but popular work, work that is not self-consciously abstract and dense and difficult, but actually is self-consciously communicable and entertaining and yet still deals with ideas.”

He thinks this is where commercial producers could step in. “Commercial theatre has been so traduced in a critical establishment which instantly is suspicious of it, and says somebody is trying to make money out of theatre [and] that is a bad thing,” he says.

“A man like [Andrew] Lloyd Webber who has been much reviled for his conservative politics – he’s a friend of mine, I don’t agree with his politics, but I do know he lives and pays his taxes in Britain and he’s put all his money back into the arts. He invests in art and theatres – that is not a way to guarantee making money.

“You want to make money, you invest in a hedge fund, and make nobody happy but yourself. Even you won’t be happy because you’ll live in a heartless town full of people like you. There will be no pubs, no clubs, no gigs because there will only be hedge fund managers and empty flats bought by overseas investors.

“We need live theatre, we need live music and for me, we need more respect for the commercial sector and for the public arts sector to be more proactive in promoting at grassroots levels, and less about high-level prestige production.”

Elton splits his time between Australia and the UK these days; he’s currently working on a new sitcom called Upstart Crow about a nerdy unappreciated Shakespeare which will soon be screened on the BBC.

In an interview with ABC TV, Elton hinted there could also be a movie in the works. Although he refuses to divulge too many details to Guardian Australia, Elton does confirm it is on his agenda: “My dream is to make a movie here in Australia. I live in Australia, I’d like to make it in Western Australia [as] I know the landscape very well. I’m quite close now, I think, to making that little Aussie movie that hopefully will punch big.”

Published on Guardian Australia on 26 April 2016 as Ben Elton: there is no wisdom involved in being massively wealthy