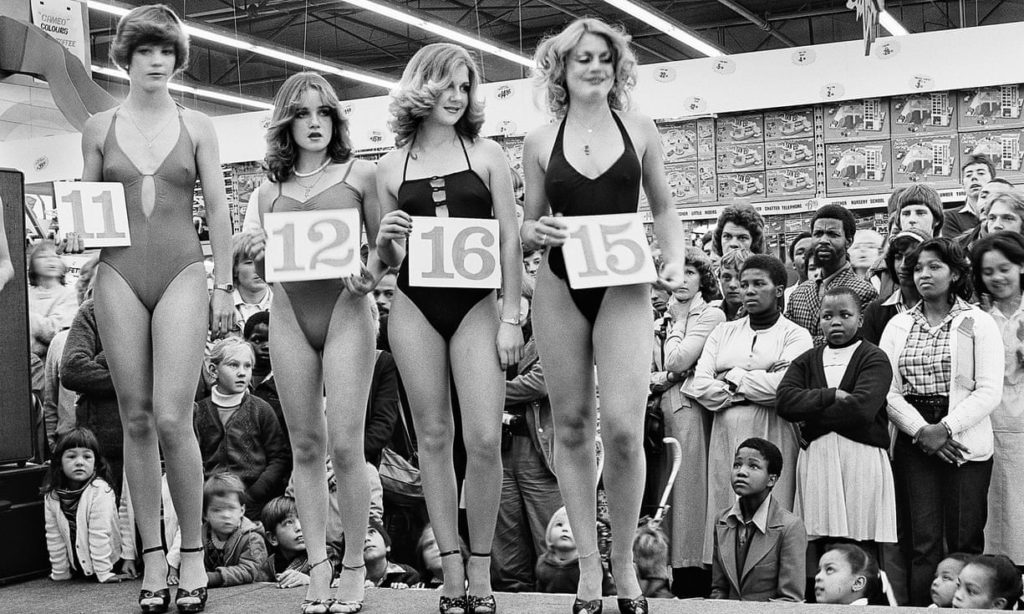

“Beauty means sexual power [and] sexual attraction. It also means that if you are intelligent, you’ve got a lot going for you,” says Charlotte Rampling, matter-of- factly. “You can get away with an awful lot when you are beautiful.”

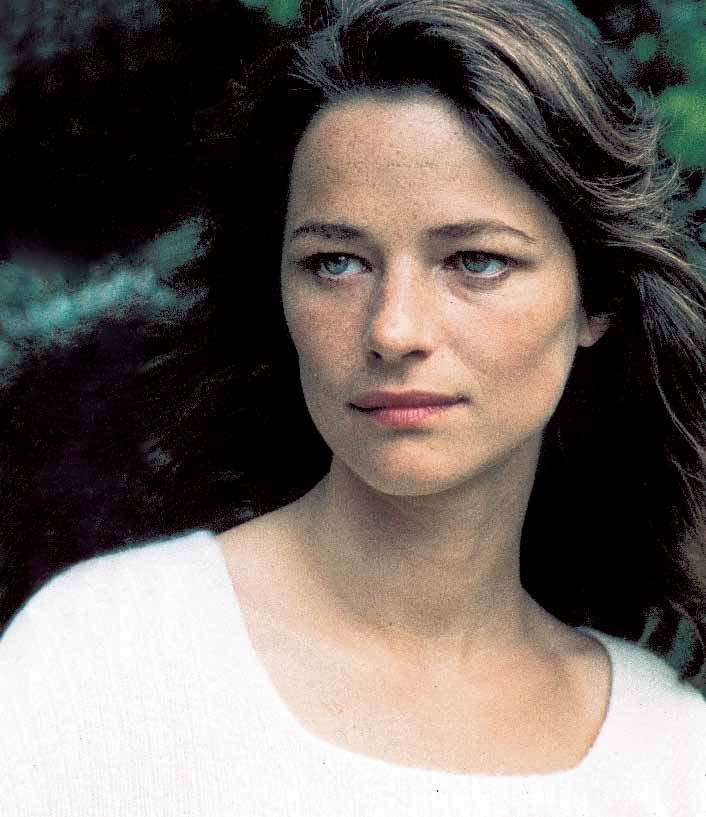

The keeper of such legendary beauty as hers is very nonchalant about its existence. In reality, her feline eyes and high cheekbones have bewitched audiences since she stole the spotlight in 1966’s Georgy Girl, but for a large part of her extensive career, she has chosen not to focus on it. “I guess not,” she muses, on the line from her home in Paris. “I thought that was too easy. I like to take the difficult road.”

On the other hand, Mrs Hunter, the character she plays in her latest movie, The Eye of the Storm, has relied on the potency of her looks throughout her life, and this intrigues Rampling. “What’s interesting with playing Mrs Hunter is you get this beautiful woman who is no longer beautiful. She is no longer a threat. She is actually on her way out, but she’s still hanging in there, she still has a spark, right until the end, and still has a hold over people.”

Based on Nobel Prize-winner Patrick White’s 1973 novel, the much-anticipated film is directed by Fred Schepisi (A Cry in the Dark [otherwise known as Evil Angels], Fierce Creatures, Roxanne) and co-stars Geoffrey Rush and Judy Davis as Mrs Hunter’s spoilt adult children, Basil and Dorothy, who rush back to Australia to attend to their dying mother. The indomitable Mrs Hunter, however, is determined to take her own sweet time.

She is yet another monstrous character to add to Rampling’s canon. “I think these kind of women are so staggeringly interesting and complex,” she says. “They’re the kind of women I suppose we wouldn’t necessarily like to be, but we secretly have some form of admiration for them, to be so out there, carrying their egos right in front, so commanding and magnetic. And they make extraordinary characters for cinema and theatre, that’s for sure.”

In fact, Rampling admires Hunter’s single-mindedness. “She lived her life really as she felt it should be lived. She’s completely politically incorrect. You could say: ‘How can we live a life like that, being so selfish?’ and yes, she was selfish, but also she had a vision and that I like.”

Rampling, 65, plays the character at both 75 and 55, an ageing up and down process that interested her. “If it was just being the older woman, I might’ve said: ‘Hmmm.’ But the fact that you have the possibility of being the two women in the same film and seeing the two faces very close when the flashbacks come in, that I found fascinating to be able to actually play.”

The film also examines the differences between the roles that children see their parents in and who they really are. This resonated with Rampling, as it reminded her of conversations with her late father before he died. “We had a few in-depth talks, only because he was a very silent man at the end, and I realised that a lot of things had been completely misunderstood.”

You could say:

‘How can we live a life like that, being so selfish?’

and yes, she was selfish,

but also she had a vision and that I like.”

She continues: “He would say: ‘But how could you possibly think that of me?’ I remember him saying, when I said he was a monster, and that I was scared of him, and he said: ‘But how could you possibly feel that?’ And I said: ‘Well, that’s what I felt most of my childhood.’ And he was heartbroken, actually, in a sense that it had been so difficult for me, but he wasn’t able to be anything else.”

She has a very close relationship with her own three children, and will soon be seen in eldest son Barnaby Southcombe’s directorial debut I, Anna. The noir thriller co-stars Gabriel Byrne, as a detective investigating a murder who falls for the mysterious Rampling, who may just be the prime suspect.

Although Southcombe didn’t write the screenplay with his mother in mind, she knew she wanted to be in it once she read it. “It was very compelling and a very interesting, well-written piece with a wonderful woman’s role.” Working with him was a joy. “There was nothing about mother and son there; it was about a director and an actor, me being part of the group as I am when I’m working,” she says.

As a child he would often accompany her on set, which undoubtedly influenced him. “I think he’s just a natural,” she says. “Whether he actually has great talent at film-making, that will be seen now, but he’s a natural in terms of how he directs people, how he works with the team, how he controls the crew. It’s like he’s done it all his life.”

She also has a small but significant role in director Lars von Trier’s film Melancholia, and she says she had a wonderful time. “I liked him enormously, I think because he’s so eccentric, he’s so unusual, he’s so special.” She had wanted to work with him since he approached her to appear in his acclaimed film Europa. “He’s very faithful with people that he likes. So he said: ‘Look, it’s not a big part, but it’s a really important part – you are going to play my mother.’” She laughs: “Here we go again, another wild woman.”

With such an extensive back catalogue, one wonders which of her films she feels best represent her. Her response is considered. “I’d choose perhaps the two [François] Ozon films Under the Sand and Swimming Pool, and then I’d probably choose The Night Porter,” she says. “One doesn’t do that many films that really somehow encapsulate [one as a person]. Those films encapsulate something about where I am in the world, I think, as an actor and as a person.”

There is something almost mythically mysterious about Rampling, which is why it is curious that she agreed to be the subject of the upcoming documentary The Look, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year. She says it took a long time for producer Serge Lalou to convince her. “We started talking and the thing started to evolve, and we found a way of doing it which was my style.”

“Those films encapsulate something

about where I am in the world,

I think, as an actor and as a person.”

The film is made up of conversations with nine of Rampling’s friends, including writer Paul Auster and photographers Peter Lindbergh and Juergen Teller. “It’s very low-key, it’s very intimate but without actually having to reveal things that are, as far as I’m concerned, not anybody’s business. It’s about life, about thoughts, about philosophy,” she says. “It’s very visual. And I have a sort of inner monologue where I’m talking about things, not really about what I’ve done but about things illustrated with film clips. It’s all very spontaneous, one stream of consciousness each time.”

She agreed to it on the basis that she would have final approval. “It’s about yourself. You have to recognise in the deepest part of your soul, you have to recognise what you’re seeing and like it, because it’s you. You can’t say: ‘Oh well, no, it’s not [me].’ If there’s a second of that, it doesn’t work because I have to accompany it and be with it and say: ‘Yes, this is what I want to say.’” And she knows the world will be listening.

Published in Vogue Australia October 2011