Goldblatt’s photographs capture the understated unease of living an ordinary life in a society that was anything but normal

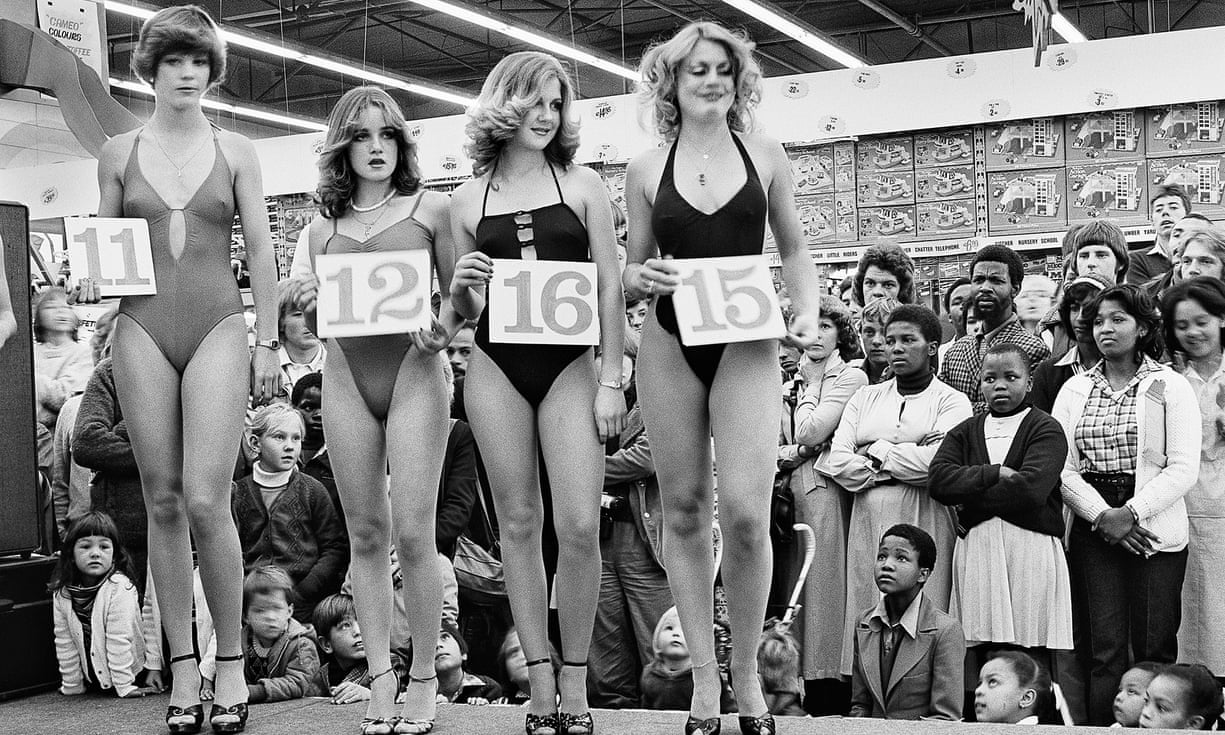

The photograph makes me squirm. Four young women, cling-wrapped in awkward swimsuits and perched on high heels, stand on display. One smirks, the other three look unsure. They clutch their competition numbers and present their naked white legs for consideration by the unseen judges.

Behind the stage, a crowd of mostly women and children cluster around the elevated stage, their faces resigned or perplexed. Dotted among the crowd, a few white men stare blankly, appraising the women’s bodies, while the only black man frowns. Most people seem bemused by the uncomfortable spectacle taking place in their local supermarket. Outside the frame, shoppers push their trolleys through the aisles, taking toilet paper and bread rolls and washing powder off the shelves.

It makes me shudder because David Goldblatt took the photograph “Saturday Morning at the Hypermarket: Miss Lovely Legs Competition” at the supermarket where my mother shopped when I was a child growing up in South Africa. And if my seven-year-old self wasn’t there on that day in 1980, I probably was later that week.

In itself, the image is ordinary. Like many of Goldblatt’s photographs, it isn’t dramatic, the subjects unknown. But it shows the casualness of a society separated by apartheid. It captures the uneasiness that pulsed through my childhood growing up in South Africa. It recalls things I saw but did not see. And it drags up the old questions that lurk beneath my memories – how could such ordinariness take place while countless horrors were happening off camera?

The image will be among many in the exhibition David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948–2018 at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art over the summer. The vast exhibition, which was planned and curated before the late South African photographer died in June this year, will include his earliest work, his later portraits of miners, of Afrikaners, of exhausted early morning commuters and those affected by Aids, as well as his numerous landscapes of meaning-laden buildings and the lumbering mines that built the fortunes of the white ruling class thanks to black labourers. Most are in black and white – Goldblatt famously said “Colour was too sweet for apartheid” – and capture seven decades of a country and people divided by racism.

Goldblatt didn’t see himself as an artist. As he told the Australian’s Tim Douglas in his last interview: “I am a photographer. I don’t hold exhibitions to glorify my artistic skill. These things I capture in my work are real. I photograph things that are important to me and to society. I want the pictures to be seen, because I want the message to be heard. But I’m not in the slightest bit interested in art and the glorification of art for art’s sake. It means nothing to me. I couldn’t give a fuck.”

Instead he saw himself as a documentarian. When asked, he explained the purpose of his photographs to his friend and colleague Paul Weinberg: “I was asking myself how it was possible to be so apparently normal, moral, upright – which almost all those citizens were – in such an appallingly abnormal, immoral, bizarre situation. I hoped we would see ourselves revealed by a mirror held up to ourselves.”

And this is what I ask when I look at his images. As Susan Sontag wrote in her essay On Photography, “The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: ‘There is the surface. Now think – or rather feel, intuit – what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.’” As I study the faces, the familiar landmarks and everyday scenes, I search for their meaning, trying, like Goldblatt, to understand. The series Particulars, where Goldblatt captures close-ups of a subject’s hands, their knees, their ears, stands out for me. As I look at them, I imagine him asking: “Where in the body does hate live? Where does love live?”

There is no violence in Goldblatt’s photograph – no schoolchildren fleeing police gunfire on the Soweto streets; no bodies strewn on the ground after the Sharpeville massacre. Just everyday life. Goldblatt wasn’t interested in those sort of images; he described himself as a coward who would “run away from violence”.

But violence permeates every life in South Africa and fear is a constant. The closest he came to examining this unavoidable reality is a series entitled Ex offenders, also part of the MCA exhibition. For this series, he photographed those who have committed a serious crime at the location where the event took place. Black and white, men and women are photographed, their wrongdoing described plainly. There’s “Blitz Maaneveld at the Terrace, Woodstock, Cape Town, where he murdered a man with whom he had been gambling”. There’s “Hennie Gerber where he tortured and then murdered Samuel Kganakga, Heriotdale, Johannesburg”. Here’s Ellen Pakkies [who] “strangled her son Abie, after his need for money to feed his drug addiction had led to him robbing the household of everything saleable for so long that she could no longer bear the strain. Lavender Hill, Cape Town.”

Like all South Africans, my family experienced violent crime: my only uncle was murdered in a burglary gone wrong, a 16-year-old neighbour raped and murdered, our home burgled three times. None of these crimes made the headlines, none were exceptional – in fact we would be considered relatively fortunate. But as I stare at the faces in this series, I feel the same old prickling of fear – and the same need to understand. These are the people that committed the terrors that haunt me and they look so ordinary. Like many in South Africa, they aren’t monsters; they’re just people who did appalling things.

I haven’t been back to South Africa for more than 20 years. The country has moved on in vast leaps but, in my mind’s eye, much of it is frozen in its horribleness, its racism, its misogyny, just like one of Goldblatt’s pictures.

But the photographs are also a powerful reminder that while ordinary people went about their daily lives, atrocities were committed and excused in their name. They are a warning that awful things happen on a normal day.

• David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018 exhibition will be on at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art Australia from 19 October 2018 to 3 March 2019

Published in Guardian Australia on 16 October 2018 as David Goldblatt’s photographs: documenting the casual horror of apartheid South Africa