There’s always the garbage bag shot. In Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, the Netflix series starring the Japanese decluttering expert turned bestselling author, there’s always at least one lingering shot of trash. Glossy plastic bags, bulging with rubbish and stacked precariously. The more bags, the better – one of the couples featured estimated they chucked out 150 full bags.

There the bags are, neatly tied up and ready to disappear, leaving the tidiers happier, healthier and relieved of all the crap they’ve been lugging around for years. It’s the shot that screams: Success! You’ve been Kondo-d! Your life is about to get infinitely better!

And it’s the shot that illustrates the problem we all have with wastefulness – which Kondo is not helping.

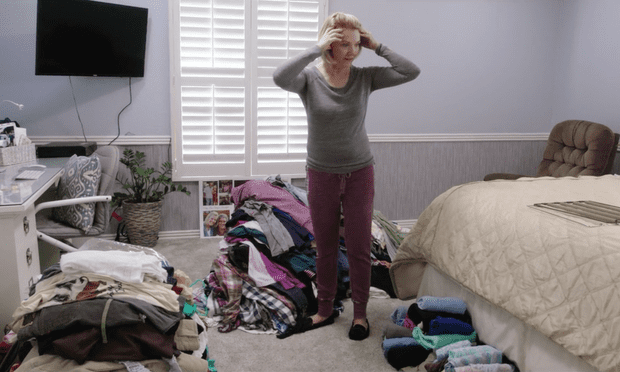

A few years ago I followed the KonMari method, the step-by-step decluttering guide laid out in Kondo’s bestselling books. It’s pretty straightforward: go through each and every thing you own, category by category, hold it close to decide whether it “sparks joy”, then discard it if it doesn’t, or store it neatly if it does.

Those three days, spent in a summery New Year haze, were an exquisite marathon purge. Clothes that I didn’t love-love, unused kitchen gadgets, mismatched crockery, reams of old documentation and countless expired skincare products all went into heavy duty garbage bags. There were bags for the charity shops, bags for the rubbish dump and boxes of books for the second-hand bookstores. The more bags I filled, the more I patted myself on the back. Then I tidied and sorted and folded whatever was left. I even mastered the dark art of folding socks and underwear.

It felt great. My apartment wasn’t exactly a minimalist heaven but I got a kick out of my well organised kitchen cupboards and my smaller pile of T-shirts stacked in descending colour order. My cutlery drawer was neater and my crockery matched – that strange, unused orange cup and saucer someone gave me was now sitting in a box outside a charity shop, waiting to spark joy in someone else.

That’s the thing though – what happens next? Where do all those bags go? The Konmari method emphasises getting rid of stuff, but it doesn’t all just vanish. We drop off the garbage bags, then forget about them as we return to our newly organised homes. Out of sight, out of mind.

Most of those op shop bags will end up in landfill, alongside the bags of outright garbage. And it costs charities millions to send it to the dump. These days landfills around the worldare overflowing with stuff that didn’t spark joy.

The idea of “don’t like it, just bin it” encourages the culture of disposability. As Eiko Maruko Sinewer, author of Waste, Consuming Postwar Japan, told me once, the Konmari method is a short-term strategy. “If you go shopping and you pick up a shirt, and that shirt brings you joy, then you buy it. Then, two weeks later, it no longer brings you joy, you can throw it away and there’s no attention to [the fact that] maybe you should have thought about the end life of that shirt when you bought it.”

We’re chucking out more than greying T-shirts and old tax receipts. While that cotton T-shirt only cost you $10, there were countless resources that went into it: the materials, the water, the energy, the labour, the transport and the packaging is all being wasted too.

And we really can’t afford to say “yeah-nah”. According to the World Bank, we are currently producing more than 2 billion tonnes of garbage each year, with that figure set to jump to 3.4 billion in the next 30 years. Landfills around the world are overflowing, with Australians throwing out 6,000kg of clothing into landfill every 10 minutes.

Recycling is not a cure-all. Last year China sparked a global recycling crisis when it closed its doors to imports of contaminated recycled material. Around the world, local councils stockpiled recycling or sent it straight to landfill.

Dumping unwanted stuff at charity shops isn’t the answer either. Only a tiny percentageof clothing donated, for instance, goes on sale. The unusable junk is sent to landfill, much of the rest is exported to impoverished countries, where it is on-sold relatively cheaply to the population. That sounds good in theory but, in reality, it can have a devastating impact on local markets, given the variable quality of secondhand clothes. It can also limit the development of local industries, and can speed up the demise of traditional clothes. Why make something original when there are cheap jeans and designer knock-off tops readily available?

There is another Japanese tradition that Kondo – and the rest of us – could embrace. It’s called mottainai. It has a long history but essentially it expresses regret at the idea of waste and reflects an awareness of interdependence and impermanence of things. Mottainai is all about reusing, repurposing, repairing and respecting items. How powerful it would have been to see Kondo chopping up old T-shirts for cleaning cloths to replace sponges or paper towels. Or perhaps she could have encouraged her desperate hoarders to repair their old shoes, bicycles and kitchen appliances, instead of turfing them?

There are plenty of alternatives to the rubbish dump for those who really can’t stand to reuse or repurpose things that aren’t zinging with joy. In Australia, apart from selling it on eBay or Gumtree, there are local swap groups on Facebook or charity groups looking to pick up unwanted furniture and clothes for those in need. It may not deliver that instant clean apartment feeling, but the goods will end up going to a better home.

Most of all, I wish Marie Kondo would just say stop! Stop buying all this stuff. The only solution to our waste crisis is to halt the consumerism clogging our landfills, polluting our oceans and overcrowding our homes. Because what would really spark joy would be a world that isn’t overflowing with garbage.

Published in Guardian Australia on 10 January 2019 as Marie Kondo, you know what would spark joy? Buying less crap