At a glittering, black-tie dinner at Guillaume at Bennelong restaurant at the Sydney Opera House, artist Michael Zavros, wearing a sharply cut tuxedo, bounds up to the podium to rousing applause. At his nearby table, wife Alison Kubler, in her sleek, one-shouldered gown, claps proudly.

Smiling broadly, Zavros regales the audience with stories of visiting Sydney from his home in Brisbane with then girlfriend Kubler during their art school days. He was young, in love and “everything was technicolour”.

Together they would explore the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), particularly the 20th-century gallery filled with his “new heroes”, the contemporary artists he was learning about. “I can remember at that time feeling this sudden hunger to be part of this, to be in this art world somehow and this desire to be a part of this collection.”

Tonight, that dream has come true. Zavros is the inaugural winner of the AGNSW Bulgari Art Award, consisting of a $50,000 art commission, along with a residency in Italy valued at $30,000.

Already a highly successful artist, with works held in private and public collections such as the National Gallery of Australia, the National Portrait Gallery and the Queensland Art Gallery, Zavros has picked up numerous art prizes, including the prestigious Doug Moran National Portrait Prize in 2010, but it’s evident from that wide smile that this is something very special.

His home in outer Brisbane is a long way from that glittering Sydney dinner. The burnt-orange hacienda-like house sits at the end of a long pan-handled driveway, which winds past long grass paddocks. Scattered around the front doorway are children’s toys and scooters.

Zavros, groomed as ever, albeit more casually in a navy blue polo shirt and black pants, welcomes me into the home he shares with Kubler and their three young children. Inside, the warm family kitchen is mirrored in the glass of an enormous Bill Henson work, and children’s finger paintings and photographs vie for attention with works by artists like Ben Quilty, Shaun Gladwell and Donna Marcus. There’s an enormous musk ox head on one wall, colourful African juju hats on another, while a taxidermied deer and a peacock and large Eau Sauvage poster by fashion illustrator René Gruau are complemented by kids’ paraphernalia. This is a home where family life jostles good-naturedly with contemporary art.

“I can remember

feeling this sudden hunger to be part of this,

to be in this art world somehow

and this desire to be a part of this collection.”

He leads me across the property to his studio, a cavernous refurbished former shed. With its white walls, concrete floors and occasional animal skin, it’s closer to what I envisaged for the artist renowned for his meticulously rendered, cool, clinical examinations of our consumerist desires. In truth, it’s a fitting metaphor for the push-pull of art versus reality, the contradictions of a working artist’s life and also the hidden depths in Zavros’s work.

We settle into two long black leather chesterfields. The coffee table is stacked with fashion magazines, which Zavros regularly draws on for his work. A portrait of a glossy black mare leans against a nearby wall, while across the studio a work in progress has been subtly covered. This is the commission he is working on for the AGNSW. All he will reveal is that it’s an interior. “Very luscious, full of detail, baroque and romantic,” he smiles.

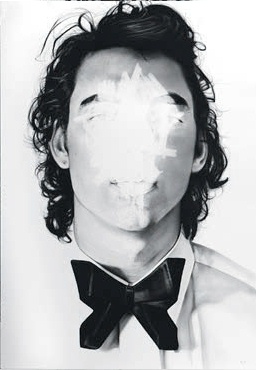

AGNSW head curator Wayne Tunnicliffe has been following Zavros’s career since the mid-1990s, after seeing a series examining shoes and men’s apparel. “Their beauty was very covetable,” he recalls, “while it also made me uneasy as it echoed the desirability of the consumer items depicted.” He watched Zavros’s progress over the years, admiring his technical proficiency as well as his choice of subject matter. “His beguiling and obviously time-consuming craft matches his exploration of desire, consumerism and the pursuit of the exceptional object,” says the curator. “He dances closely with an art that holds itself aloof from the world depicted as it suggests its inherent narcissism, while being obviously fascinated by that world.”

When Bulgari proposed the award for a mid-career artist to the AGNSW, Zavros was top of Tunnicliffe’s list. Thrilled to be included, the artist responded with ideas he was currently exploring. He had long been fascinated by interiors, visiting grand European palaces whenever he travelled, describing them as soulless museums to those long gone. “They’re all about the figure in absence.”

And so the Bulgari commission will not be dissimilar to other Zavros works. “It references a lot of different elements in my practice,” says the artist. “It covers a lot of where I’ve come from and hopefully where I’m going.”

Zavros began drawing when he was very young, sketching animals for his parents. He would spend hours drawing on his own. “If you have that visual retention where you can draw something, you want to hone that and perfect it.” He attended Queensland College of Art, quickly realising that technical ability wasn’t valued as much as creativity and that what he was painting was more important than how he was doing it. “What makes a good artist is the choices that you make.”

A natural aesthete, he admits he has always been obsessed with how things look. “I love looking at beautiful things. I always have, in a classical sort of way.” Yet none of his contemporaries seemed interested in creating anything beautiful. “It seemed anathema to contemporary practice. It was just uncool really and so was painting, particularly realist painting.”

Yet he stuck to his path and, particularly in the last few years, his practice has been about more than just exquisite craftsmanship. Although he has long explored the dilemmas of consumerism, art critics have noticed works like Body Lines (2011), for example, have ventured into political territory, without necessarily being didactic. “You’re asking questions, rather than offering answers,” says Zavros. And then there are works, such as The Python (2011), which offer a commentary on how his own work has become a trophy in itself. “So much of my work is critical of the thing that it embraces. It seems to trade in desire but it has a critique as well.”

With his handsome, urbane looks and accessible works, he’s fast becoming one of the art world’s favourite poster boys, a position that both amuses and bemuses him. “I’m guilty of having all those desires and my work feeds into that. I want the things that I paint,” he laughs. Yet it’s a very one dimensional position, and reality is living on a property in Brisbane surrounded by kids and horses and chickens. “When I go out, I like to put on a tailored suit or a nice pair of shoes, but for weeks I’ll just be here, looking like hell, living and working on the property. That’s more who I am, but I would never be perceived that way.”

“So much of my work is

critical of the thing that it embraces.

It seems to trade in desire

but it has a critique as well.”

He laughs when asked why realism continues to fascinate him, particularly in the age of digital photography. “I could give you lots of good answers about the relevance of realism, but I know the really honest answer is because I can.” It’s always been about creating beautiful work. “It just makes me feel happy that I can do this. We all like to be good at what we do and that’s one thing that I feel like I can be confident in doing.” He’s always searching for ways to make realism relevant. “It’s funny to be doing this at a time when it’s so pointless, when we can take photographs,” he says. “It’s such a romantic, silly thing to be doing.” And yet so wonderful.

Published in Vogue Australia August 2012

WHY DON’T YOU READ:

Artist Martine Emdur’s new work is tantalisingly seductive

Hobart’s MONA is an experience never forgotten