From above, the vast terrain looks like wrinkled elephant hide dotted with tufts of palm trees and thick clumps of savannah grass, but up close the white sand of the Makgadikgadi salt pans of the Kalahari desert, deep in the heart of northern Botswana, is cracked like a lunar landscape.

It feels like we have travelled to the moon. After one lengthy long-haul flight, a bumpy domestic one and then a charter flight in a small Cessna that bounced across the thermal air currents, it’s good to be on solid, albeit foreign soil.

And it is distinctly foreign. Dust billows, the air is dry and the wraparound horizon is softened only by scrub and low-slung trees. As we bump along the well-worn tracks, wildebeest lazily regard us as the curiosity.

Up ahead is the cool respite of the mirage-like white tents of San Camp. Our hosts, owner Ralph Bousfield and his nephew, manager Rob Barclay, greet us warmly as we dismount from the open-air jeeps that whisked us from the airstrip. They lead us into the main tent, where we sink back against Moroccan cushions, our hot, swollen feet deliciously bare against the thick Persian carpets, to sip cold homemade lemonade and snack on freshly baked cookies.

Their family has lived on this land for six generations, and the camp’s gracious simplicity is made personable by a sense of being welcomed into their home. The high four-poster beds in the guest tents are plump with linens and deep pillows, ornithological and botanical drawings decorate the walls of the tents, and family photographs and mementoes top polished wooden dressing tables and chests of drawers.

Yet there is no escaping the isolation and remoteness of the area. Bousfield tells us about his crocodile hunter father Jack, who discovered this spot in the 60s (and after whom the neighbouring Jack’s Camp is named).

He was deeply affected by the true wildness of the area. “There is a great quote that sums up both my father and the area,” he says. “It is: ‘Makgadikgadi … what is out there?’ he asked, and they said: ‘Nothing. Only idiots go out there’ and he said: ‘That’s the place for me.’”

As empty as the terrain appears, it is teeming with life. The next morning, as we head into the national park in the jeeps, birds caw-caw overhead, a mongoose bounces out of sight and a family of ostriches gallop in the distance. We stop to visit a family of meerkats, who ignore us until we crouch down in the dust to provide them with an even more advantageous lookout, and they skip up to perch on our heads.

Palm trees trampled by elephants, a cow carcass and strange barking in the dark night hint at wilder animals just beyond the frame. “There’s that certain feeling of wildness where you know it’s just that fabric between you and that thing out there,” says Bousfield. “We’ve spent hundreds of years distancing ourselves from nature. We are an African mammal but we’ve been in denial, thinking we’re not part of this.”

There is a sense of timelessness about this ancient land and many things are as they have always been. The indigenous Bushmen still hunt and gather their food as they have done for centuries, while other traditional communities live in mud hut villages, guarding their corralled cattle overnight from the ever-present threat of lions.

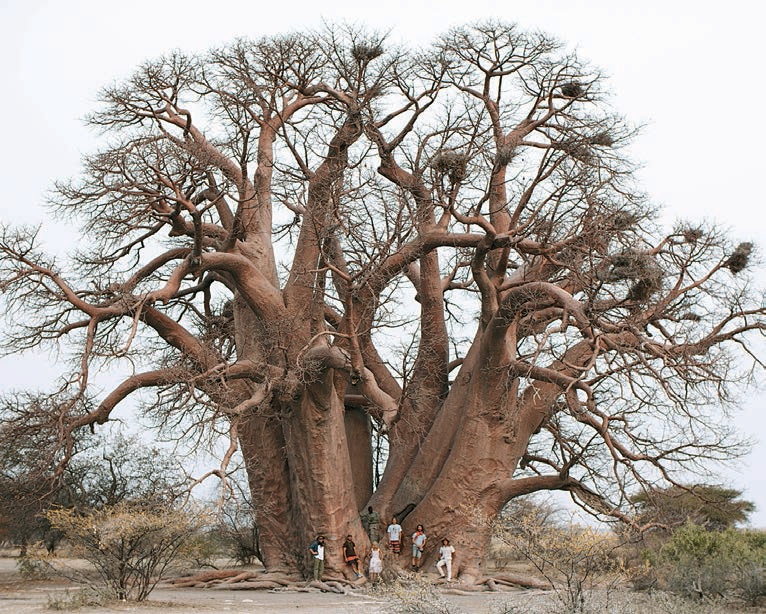

Early European travellers have also left their mark. As we travel along it, Bousfield tells us that Missionaries Road was one of the first tracks through the centre of Africa. One of the local landmarks is Chapman’s baobab, an enormous, seven-stemmed baobab tree named after a 19th-century explorer and said to be thousands of years old. The tree was used as a post office for wagonloads of early missionaries, explorers and traders, who often scored its magnificent trunk with still-visible signatures.

There is something about being out in the middle of nowhere, dwarfed by space and history, that gives pause for reflection, something that makes you stop for a moment and realise how insignificant both you and your niggling worries are. Or perhaps realise what is truly important. Like a steaming hot shower by the light of a kerosene lantern after a dusty day; the sense of snug security when buried deep beneath the covers at midnight; or the warmth of freshly brewed tea against a bitterly cold dawn as the sun rises reliably the next day. Bousfield agrees: “There’s something about the place where people kind of come to terms with themselves.”

The absence of distractions and the vastness of the land gets under your skin. “It’s not that this is a place where you are going to come and have to deal with your demons, but it’s just a place where you go: ‘Actually, this is quite comfortable.’”

San Camp only operates for six months of the year, before the rains and the great migrations of zebra and wildebeest across the pan. The impermanence lends it a special quality. “It gives it that edgy feeling. You know that within a month, this is going to be gone,” says Bousfield. “And then next year we’ll come up and we’ll put it up again, but it’s never quite the same.” Only the ancient land persists.

Visit www.unchartedafrica.com for more details. To book, visit www.classicsafaricompany.com.au.

Published in Vogue Australia December 2011

WHY DON’T YOU READ:

The ever surprising California

Hobart’s MONA is an unforgettable experience